During lunch Marsha asked if we might finish up quickly so she would have time to tour the mammoth exhibition hall that was attached to the conference. With no events scheduled during the lunch break, the hall was packed with therapists, academics and researchers moving about hundreds of tables that were promoting every mental health product or service imaginable. Almost every exhibitor offered some sort of trinket that was free for the taking.

Among the pens, pads, pins and buttons were a number of squeezable rubber – supposedly stress relieving¬– items; soccer balls, globes, toucans and so forth. One caught my attention, a highly detailed version of a human brain that fit neatly into the palm of the hand, ready to be wrung when needed. These were cute, kitschy and probably the least useful items there, but conference attendees were scooping them up and stuffing them into swag bags by the fistful. It was a bit surreal – accomplished, successful, intelligent professionals, glomming these little rubber brains whose primary value, as best that I could surmise, was that they were free.

Among the pens, pads, pins and buttons were a number of squeezable rubber – supposedly stress relieving¬– items; soccer balls, globes, toucans and so forth. One caught my attention, a highly detailed version of a human brain that fit neatly into the palm of the hand, ready to be wrung when needed. These were cute, kitschy and probably the least useful items there, but conference attendees were scooping them up and stuffing them into swag bags by the fistful. It was a bit surreal – accomplished, successful, intelligent professionals, glomming these little rubber brains whose primary value, as best that I could surmise, was that they were free.

The memory of those little sponge rubber brains brought to mind a phenomenon that was just emerging in the research literature around that time– neuroplasticity. What is neuroplasticity? According to the 2005 Annual Review of Neuroscience, neuroplasticity refers to structural and functional changes that can occur in the brain due to changes in a person’s behavior, environment, thoughts and emotions; as well as changes resulting from illness and head injuries This was quite a dramatic shift from the traditional belief that once a person’s brain fully matured in adolescence it basically remained unchanged for the rest of that person’s life.

But it turns out that the neurons, or nerve cells, in our brains actually have the capacity to regenerate and in the process improve and potentially restore neurological function.

How does that happen? For one, apparently medications can stimulate the creation of new brain cells – it’s called neurogenesis- and that helps form new pathways for brain activities, providing the brain with more ways to moderate the causes and effects of mental illness. This is particularly helpful in the treatment of depression, anxiety and impulsivity.

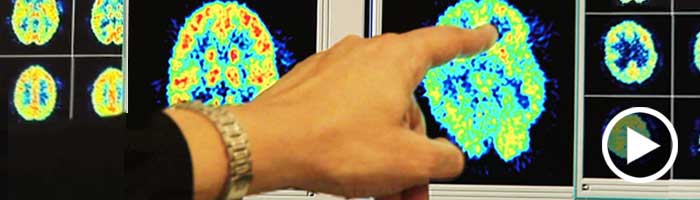

In addition, research over the past ten years has demonstrated that non-drug interventions such as talk therapy can also result in physical changes in the brain. Using state-of-the-art image technologies, a number of studies looked at which areas of the brain are affected during and after therapy, and how these changes lead to symptom reduction and overall improved functioning.

Documented findings that the structure and function of the brain can be enhanced through medication and talk therapy are certainly cause for optimism. But positive outcomes are not a simple matter to accomplish. Recovery from a mental health condition is a slow and frequently frustrating experience; recovery is a long-term process marked by several steps back for every step forward. It takes courage, determination and discipline to get back on your feet after each knock down. And in recovery there are many of those. To hear a first hand account of what the process of recovery can be like, please read this article posted on Across the Borderline. It’s a frank and compelling description of one woman’s journey to well being. Source: The Plastic Human Brain Cortex,Annual Review of Neuroscience, Vol. 28: 377-401